The Jump: A Comparative Case Study of Suicide in Architecture

Due to the delicate nature of this essay’s topic, I will provide resources for those who need them:

988 | U.S. Suicide and Crisis Lifeline

(801) 587 – 3000 | Utah Crisis Line

My intention with writing this essay is not to be callous towards those who ponder suicide. Should it come off that way, I apologize in advance. Now on to business.

"There is but one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide. Judging whether life is or is not worth living amounts to answering the fundamental question of philosophy."

-Albert Camus

Introduction

Humans have free will. After all is said and done, the individual who chooses to kill himself does so out of his own volition. Ethically speaking, he is solely responsible. This does not imply, however, that others are unaccountable in guaranteeing his continued existence.

The built environment’s omnipresence extends to the furthest reaches of the mind; it is a crucial determinant in him who is contemplating suicide—even if he himself is not cognizant of it. To illustrate this, I have selected two structures—the Vessel and the Guggenheim Museum—to compare architecturally and philosophically. I have chosen these two in particular because they share similarities in geographic location, populations served, and physical design. Nonetheless, they diverge in one key area: the Vessel has a string of suicides that Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim does not.

Prior to undertaking any architectural analysis, I will establish a definition of suicide and explain the philosophical rationale that precedes it.

A Suicide of Anguish

Suicide can be organized into three categories based on its underlying motive. These are a suicide of anguish, a suicide of faith, and a suicide of convenience.

A suicide of anguish is what typically comes to mind when thinking of the term. It is a killing of oneself due to an excess of suffering. When an individual cannot derive any philosophical justification for existing in spite of suffering or when belief in his justification is temporarily suspended, he may commit a suicide of anguish. Oftentimes, this follows a period of egonihilism, (see “The Eternal Optimist” for a definition of egonihilism) where the self depreciates until it is deemed worthless.

A suicide of faith is a killing of oneself with the sincere belief that it is the correct path forward. The mass suicide of the Heaven’s Gate cult would fall under this category, as would the suicide of the nihilist who genuinely believes that life is meaningless and thus ends his own, not as a matter of emotion, but as a matter of logic.

A suicide of convenience is a killing of oneself purely for utilitarian purposes. For instance, consider Smerdyakov’s suicide in The Brothers Karamazov, which was done to avoid having to testify and suffer for patricide. A CIA agent using a cyanide pill to avoid interrogation falls into this category as well.

The first case (a suicide of anguish) is what will be meant by the word “suicide” for the remainder of this essay.

Concerning its rationale, life is an amalgamation of suffering and happiness. When suffering becomes excessive—or is perceived to be excessive—the individual questions if he can endure, and moreover, what the purpose in doing so would be. Precisely at this moment, his philosophical character will determine his fate.

Instead, he is trapped in a spiritual limbo, the cognitive dissonance of which, in combination with the torment of his circumstances, drives him to self-termination. Knowing this, the design of a building must invoke either the spirit of rebellion or the spirit of submission. How this physically manifests differs for every building, but it must be present. The Vessel conjures neither spirit, hence it fails to prevent suicide, while the Guggenheim Museum succeeds in doing so. The object of analysis, then, will be to elucidate why this is the case.

Origin and History

The circumstances in which a building is conceived affect its occupants’ perception and opinion of it. If exploitation, deceit, greed, megalomania, or other corrosive vices plague its backstory, so to speak, then its design must work that much harder to overcome its origins. And should its design be tenuous and inferior, then the rotten qualities of its birth are exacerbated. A structure’s biography is a crucial facet of any architectural analysis.

The Vessel

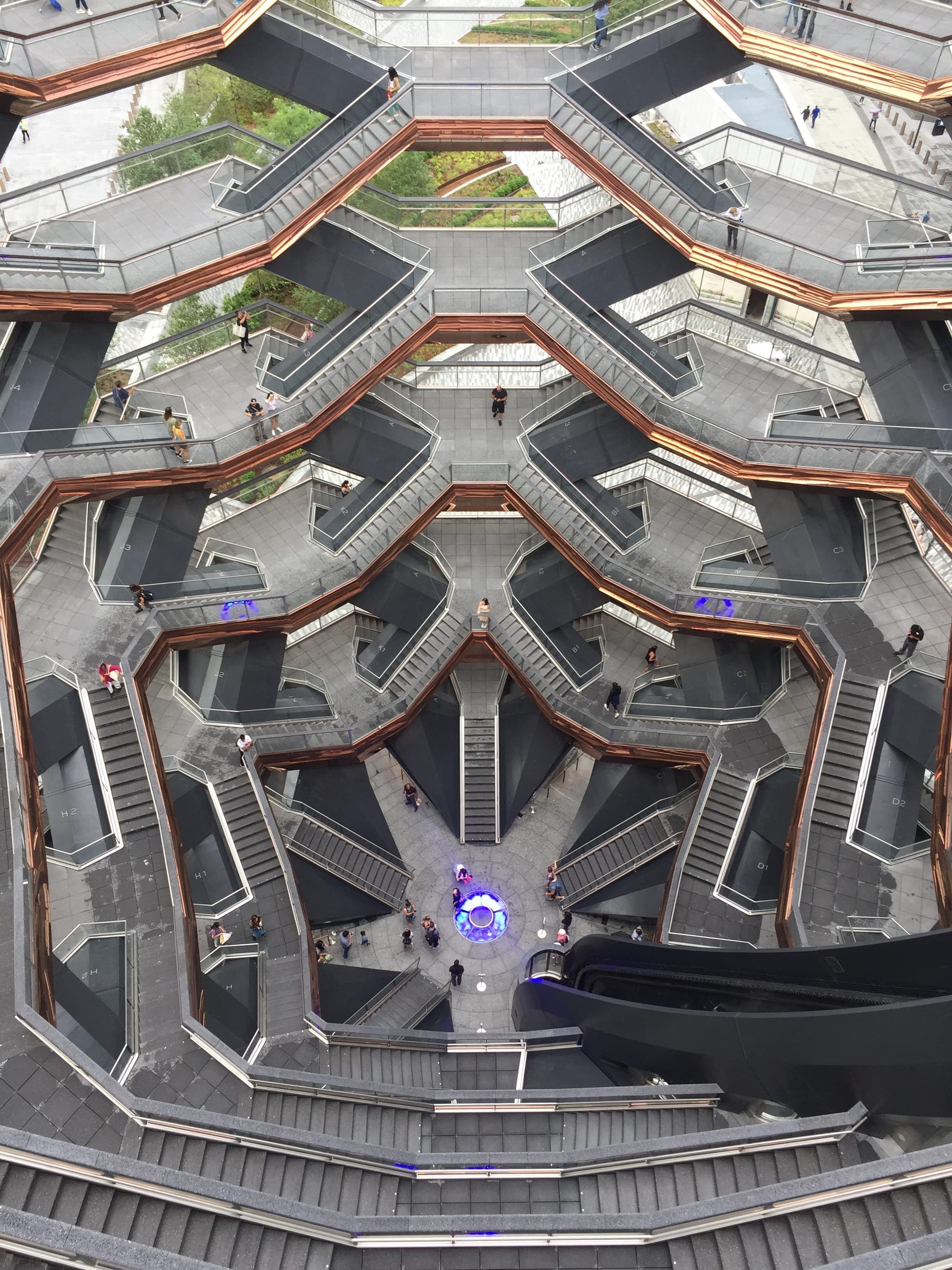

Devised by British designer Thomas Heatherwick, the Vessel is a steel wireframe structure akin to a honeycomb, but rather than containing sweet honey, it is filled with bitter emptiness. Located prominently in the Hudson Yards development of New York City, it consists of one hundred fifty-four flights of stairs across sixteen floors [1]. The development, and, by extension, the Vessel, is funded by Stephen Ross, the billionaire and former CEO of the Related Companies, a notable real estate firm founded by him in 1972 [2]. The Vessel acts as the centerpiece of Hudson Yards, dreamed by Ross to be the “Eiffel Tower” of the twenty-five-billion-dollar development [3]. The discerning reader will come to find out over the course of this essay that the Vessel is in fact not a dream, but a dystopian nightmare.

The Vessel opened to the public on March 15, 2019. On February 1, 2020—slightly less than a year later—a nineteen-year-old man jumped to his death from the sixth floor of the structure [4]. Three more suicides followed:

- A twenty-four-year-old woman, on December 22, 2025 [5].

- A twenty-one-year-old man, on January 11, 2021 [6].

- A fourteen-year-old boy, on July 29, 2021 [7].

Four individuals whose stories were unnecessarily cut short.

The Related Companies convened with designers and suicide prevention experts. It implemented several minor precautions such as requiring all visitors older than five to purchase a ticket (access was previously free) and be accompanied by at least one other person [8]. Note that the last suicide (that of the fourteen-year-old) occurred after these measures were put into place. Numerous commentators and experts suggested that higher railings would easily solve the problem, but this was rejected on the basis that it would impede the design. I have no doubt that better railings would work, but it is a brutish solution that neglects the crux of the issue.

How to correct it is the pertinent question. Before answering that, I will describe the inception of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

The Guggenheim

Designed and constructed by architect Frank Lloyd Wright between 1943 and 1958, the Guggenheim is a museum of modern and contemporary art. A wealthy businessman, Solomon R. Guggenheim commissioned the building using a fortune amassed from inheriting and expanding his family’s mining businesses. Later in life, he became a distinguished art collector. His collection eventually grew so large that it necessitated the construction of a proper museum.

In its sixty-six-year history, not a single individual has ever jumped to his death from the Guggenheim, despite it having a “great rotunda” (as Frank Lloyd Wright called it) that rises through six levels, with low-lying railings that are a trifle to scale. Moreover, the Guggenheim is located just four miles away from the Vessel and serves a similar demographic, as the individuals jumping from the Vessel are the same individuals who would otherwise ordinarily visit the Guggenheim. Both structures are the product of wealthy businessmen, and both have spiraling designs. Parallels notwithstanding, the Guggenheim speaks directly to the humanity of its occupants, whereas the Vessel concerns itself solely with its own features.

Substituting Money for Ideas

Frank Lloyd Wright said of New York City:

"It is a great monument to the power of money and greed, trying to substitute money for ideas." [9]

This notion sums up the essence—or lack thereof—of the Vessel perfectly. This will become obvious as I undertake a rigorous analysis of both buildings. A building always begins as an abstract representation of a goal, idea, or principle (its teleology), which is then made concrete.

The Vessel

The Vessel’s framework is constructed from painted steel members. One hundred fifty-four flights of stairs are arranged around the frame such that they create an upside-down beehive shape. The structure is clad with a polished, copper-colored steel veneer that gives it the appearance of cheap jewelry. Each flight of stairs has a glass balustrade with a thin metal banister to exemplify the viewing experience. The overall style of the structure is garish, a monument to opulence with no philosophical substance to be found. The building makes a parody out of the depth and beauty intrinsic to human life, with a two-hundred-million-dollar price tag [3].

But more troublesome than the aesthetics is the absurdity that arises from the Vessel’s complete lack of function. It is painfully clear in its utter uselessness. Imagine, if you will, that you approach the base of the “sculpture,” anticipating what purpose it could have in store. You ascend the first flight of stairs and descend the next to see that you have ended up nowhere at all! Appropriately confused, you resolve to only ascend, believing that the pinnacle of this geometric novelty must have something of value. And so you begin your climb. You walk up one flight of stairs. And the next. And the next. And so on and so forth. Finally, you reach the tenth floor (or so you suppose, as you have lost count) and take a moment to observe your surroundings. The entire structure looks identical throughout; you have no conception of where you started or where you are headed. You do notice that the people below are walking about with ostensibly no aim in mind. Begrudgingly, you ascend the last six stairs and behold the zenith of your labor: the New York City skyline. A view. Yes, that is all there is at the top. Tired and disappointed, you wonder if the vista is better on the opposite side. You gaze across the central atrium and discover that you will have to mindlessly ascend and descend even more stairs simply to make it over there. You realize you have been gamed. There is no end goal. No purpose. Endless effort, zero destination. All you have accomplished is wasting your time on a billionaire’s fantasy, panem et circenses.

Dear readers, it is a mockery of the ordinary man’s way of living! And therein lies the whole conundrum. Not only is the Vessel devoid of any significance beyond its flashy shell, but its absurdity makes it detrimental to human life. I believe this is the first example in history of “Sisyphean” architecture. Recall that Sisyphus’s punishment for foiling death was to push a boulder up a mountain only for it to roll back down as it neared the peak, ad infinitum.

Whether intentional or not, the Vessel is a punishment for its visitors; for what transgression I cannot say. Quite unlike the Guggenheim which is a cultural gift to the people of New York City.

The Guggenheim

The Guggenheim differs from the Vessel in its materials, function, and teleology. Its organic spiraling form is made possible by its construction from reinforced concrete and steel rebar. It exhibits a simple, white façade, a stark contrast with the Vessel’s ostentatious but cheap exterior. The Guggenheim’s mien does not alienate any constituents of its demographic, rich or poor. Its clean, modern demeanor uplifts the individual rather than making him feel small and insignificant.

The building displays artworks in a fluid manner to evoke and encourage movement in the viewing experience. The architecture supplements the otherwise static art with mobility, linking each piece to the next, thereby creating a cohesive whole that can truly be called a museum of mankind’s creativity. And in connecting each individual artwork, so too is each individual person connected with another. The unity of mankind established firmly in stone and steel. Separate individuals, one whole. The Guggenheim excels at its objective. Its functional clarity demolishes the Vessel’s sheer absurdity.

The most foundational aspect of the Guggenheim is its teleology. Frank Lloyd Wright designed it with the metaphysical purpose of loving humanity. In essence, this was Wright’s goal for all his buildings. Organic architecture emphasizes a harmonious connection with nature precisely because he believed it to be the most efficacious way of loving his fellow man.

The physical qualities of a building proceed from its teleology. If there is no telos, then the design choices are arbitrary. They have no weight. The Guggenheim’s telos manifests through phenomenology. The soothing simplicity of the pure white walls coupled with the softly spiraling walkways takes you on a voyage through the artistic achievements of your colleagues. You cannot help but feel love towards the humanity within yourself when presented so elegantly with the beautiful end products of human potential. In this way, the Guggenheim is a remedy for the internal turmoil of the individual contemplating suicide.

Buildings as Philosophical Remedy

As mentioned above, the design of a building starts out as a cognition of philosophical principles and artistic themes, from which point it manifests on the drawing board, proceeds through iteration, and becomes reality on the site. It is at the preliminary stage of cognition that the architect imbues the building with its philosophical significance. The nature of this significance has an observable effect on whether an individual will select the building to commit suicide.

The Vessel

When analyzing the Vessel philosophically, it is immediately obvious why it has a proclivity for attracting suicides. It is a scarab, a glitzy carapace with no internal substance. Its materialism and absurdity, along with its plutocratic origin, violate the inherent dignity of the individual. The Vessel mirrors the futility of existence in a society that disrespects individuals by treating them as merely a means to an end, rather than as ends in and of themselves. As such, the individual regresses to a state of egonihilism. When the ego (the self as distinct from the world) is eradicated, suicide becomes permissible, and perhaps even inevitable.

The Guggenheim

The Guggenheim’s focus on human creation positions it as an antidote to egonihilism, and, consequently, suicidality. It is a loving testament to man’s ability to produce beauty in a universe enveloped in chaos. The museum is a respite from the ugly torments that many individuals find themselves surrounded by.

Designing to Save a Life

A building must be constructed with the intent of loving humanity. The actual design of the structure (form, color, material, etc.) arises in the pursuit of seeing this intention fulfilled. But without that particular teleology in place, the building will inevitably work against mankind.

I have been extremely critical of the Vessel and Heatherwick’s design because architecture should never push an individual to end his own life; there is no consequence more anti-human than that (aside from creating architecture that is intended to kill, of course). And while Heatherwick may see himself as irresponsible for how people use his creation [10], it is very much within the purview of the architect to ensure that his buildings are being utilized to their proper effect. So what exactly can be done to correct the Vessel’s issues?

Start first and foremost by giving it a productive function. Any tall building can provide three-hundred-sixty-degree views from its rooftop without being alienated from utilitas. Picture, for example, the Vessel as a ziggurat with a garden and seating space on each level—akin to the Hanging Gardens of Babylon.

From here, the aesthetics can then be improved. A structure made of stone, wood, and concrete would amend the current look of worthless spectacle. Pair this with recessed relief carvings on the façade to exemplify the painstaking art of sculpture and man’s capacity for precision and detail in his edifices devoted to culture. In doing this, the sheer craftsmanship of the building would be a beacon of human brilliance and would engulf the city with the spirit of rebellion.

Unfortunately, the Vessel, as it currently stands, is a monument to excess luxury and a mockery of the ordinary man. It was built without the ideal of love and therefore is a catalyst for suicide. But know that through a loving architecture one can, in fact, build to save a life.

References

[1] Bockmann, Rich. “Stairway to Hudson: Related unveils $150M sculpture”. The Real Deal. September 14, 2016. https://therealdeal.com/new-york/2016/09/14/stairway-to-hudson-related-unveils-150m-sculpture/

[2] Brennan, Morgan. “Billionaire Stephen Ross Steps Down As CEO Of Related Cos”. Forbes. September 7, 2012. https://www.forbes.com/sites/morganbrennan/2012/09/07/dont-expect-much-to-change-as-billionaire-stephen-ross-steps-aside-as-related-cos-ceo/

[3] Tully, Shawn. “This Monument Could Be Manhattan’s Answer to the Eiffel Tower”. Fortune. September 14, 2016. https://fortune.com/2016/09/14/stephen-ross-eiffel-tower-hudson-yards/

[4] Parnell, Wes. “Teen leaps to death off Hudson Yards Vessel”. New York Daily News. February 2, 2020. https://www.nydailynews.com/2020/02/02/teen-leaps-to-death-off-hudson-yards-vessel/

[5] Garber, Nick. “Woman Jumps To Her Death From Hudson Yards' Vessel”. Patch. December 22, 2020. https://patch.com/new-york/midtown-nyc/woman-jumps-her-death-hudson-yards/

[6] Rayman, Graham. “Man, 21, jumps to death from the Vessel at Manhattan’s Hudson Yards”. New York Daily News. January 11, 2021. https://www.nydailynews.com/2021/01/11/man-21-jumps-to-death-from-the-vessel-at-manhattans-hudson-yards/

[7] Parascandola, Rocco. “Teenager jumps to his death from the Vessel at NYC’s Hudson Yards”. New York Daily News. July 29, 2021. https://www.nydailynews.com/2021/07/29/teenager-jumps-to-his-death-from-the-vessel-at-nycs-hudson-yards/

[8] Cuozzo, Steve. “Hudson Yards Vessel bans individual visitors after rash of suicides”. New York Post. May 25, 2021. https://nypost.com/2021/05/25/vessel-set-to-reopen-with-no-single-visitors-allowed-after-suicides/

[9] Wright, Lloyd Frank. “Frank Lloyd Wright Interview”. The Mike Wallace Interview. 28:35 - 29:12. September, 1957. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DeKzIZAKG3E/

[10] Heatherwick, Thomas. “The Vessel: Thomas Heatherwick's oversized public art structure”. CBS Sunday Morning. 5:00 - 5:12. March 17, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gy4Sg6cWGgc/